Imagine you’re a profit participant in John Carter. You’re not going to see any money, but you are entitled to “Participant Statements” from Disney. What do those statements look like? What do they reveal?

I have not seen an actual participant statement for John Carter. But I have seen statements by Disney for other films. One is a Participant Statement for the film Ransom, directed by Ron Howard and starring Mel Gibson.

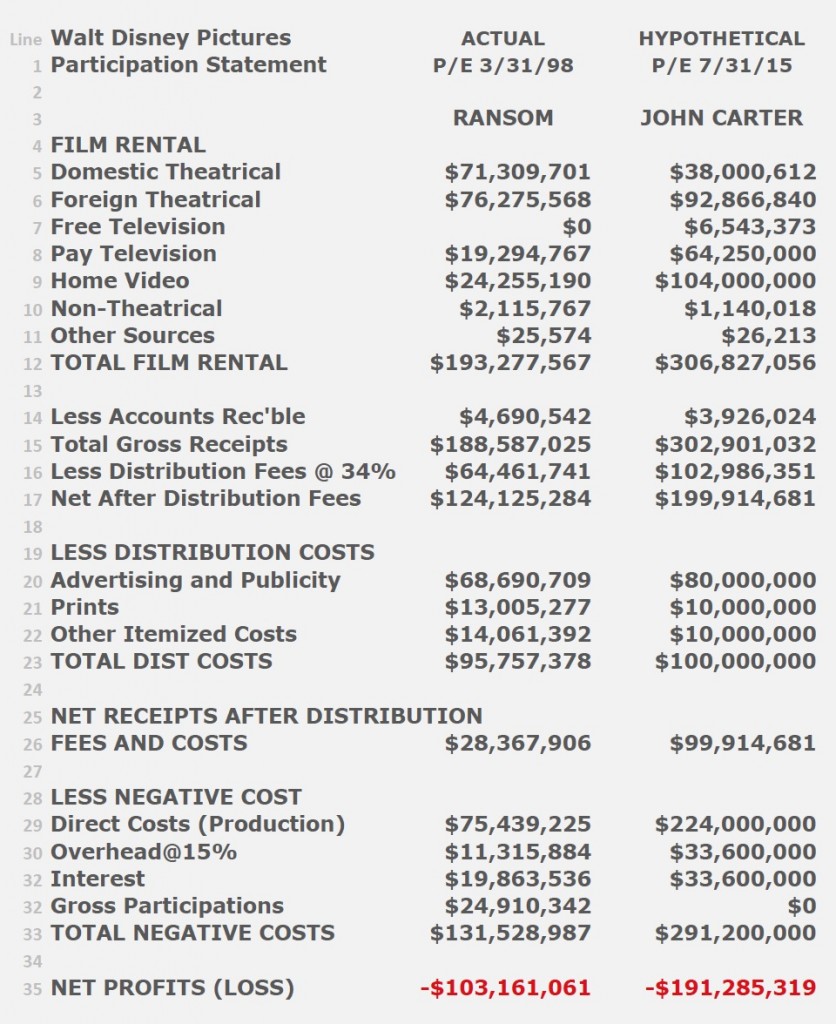

So last night, having nothing more productive to do, I had the brilliant idea of taking the Ransom statement and using it as a template to do a John Carter statement — using all the known data on John Carter, plus setting up algorithms based on the figures in the Ransom report — i.e. the relationship between the various elements, percentage wise, — applying the same percentages to John Carter where that approach made sense, or using known figures when that made sense. Sound confusing?

So while watching the Dodgers take care of the Nationals on the tube, I worked through it all from top to bottom, using all the data that’s available and modeling it on the Ransom statement. I had no idea whether, when I got to the bottom line, it would track with Disney’s announced loss of $200M. But — magically it seemed — when I got to the bottom and hit “Sum” on my excel sheet — the number that popped up was a loss of (-$191,285,319) which is very close to Disney’s announced loss. I decided to stop right there and not do any tweaks …. so here it is, with discussion of it after the chart:

One word of caution — “Film Rental” is the net to the studio from Box Office Gross after the exhibitors take their cut. Think of it as “Box Office Net”….. so that’s why you see theatrical of $38m instead of 74m for domestic, and 93M instead of $211M for foreign.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Now let’s go through the chart.

FILM RENTAL

As noted above, film rental is the movie industry term for film income after theaters have taken their cut. In the case of Ransom, the box office gross was$136,492,681 Domestic — so the $71,309,701 reflected 52% of the domestic total — so for JC, I’ve used the same formula, showing $38M++ which is 52% of the BOG of 74M. I did the same for foreign — modeling the percentage (42% in the case of foreign) on Ransom. In both cases these percentages could be off a little because it varies from film to film, deal to deal. Realistically I think this as about as good a split as JC could hope for.

For the other numbers like Pay TV and Free TV I’ve used the average figures and/or have derived percentages from Ransom, or split the difference. The TV income doesn’t add up to 28% yet because it’s still coming in and will continue to come in for some years. The home video amount is very generous to JC — I don’t see how it could be much more than that, but I made it generous because of the perception among fans that it did really well in home video, and I didn’t want the model to be light in that area.

So you end up with total revenue to date of $$306,827,056. That’s not the final revenue figure — but it’s probably 80% of it or even 90% at this point.

Now…deduct A/Rs and that gives you total gross receipts of $302m.

Now, here comes the first nice big bite — 34% distribution fees. This is the fee taken by Buena Vista Distribution, which is a different entity from Disney Studios, the producer. This is in essence what Disney Studios pays to Disney Distribution for the work it does in distributing the film. And this is just the work — not the out of pocket expenses. They should call it “Distribution Overhead” but they don’t.

So — $102M went into Disney’s bank account but it was BV Distribution’s bank account, so Disney gets to treat this not as income, but as a cost — because it is a “cost” to Disney Studios, the producer or owner of the film. Does that make sense? Of course not …ah, but it does, in a diabolical way. You see, if you produced a movie with your money and took it to Disney Distribution and they distributed it — of course they would be entitled to a distribution fee for that service. So when Disney Studios gives them a movie to distribute — they still expect to make their distribution income. And even though this is income ot the larger Disney corporation — it’s booked as a cost against the film borne by Disney Studios, the owner.

That’s not all.

DISTRIBUTION COST

Now look at lines 19-24 — Distribution Costs. These are expenses paid by the distributor, traditionally called “Prints and Advertising” or “P and A”. The distributor gets to recoup these in full prior to any money going back to the producer. This is where you hear the famous movie phrase: “Didn’t recoup P and A” — meaning a film didn’t make enough to even recoup this money, much less the production budget. In the case of John Carter, the film does recoup P and A … and there is $99K++ left to apply against the production budget plus interest, plus overhead.

NEGATIVE COST

So that takes you down to the bottom. “Negative Cost” means the cost to produce the finished film negative, before paying for prints and advertising. The 99k gets applied against that, which we know to be $$307M minus $43M British Tax rebate, for a net production cost of $264M. This is where you also see the famous “Studio Overhead” charge of 15% of production cost, which is not a real direct cost but is John Carter’s share of Disney Studios’ overhead, and interest charges on the money.

BOTTOM LINE

The bottom line here matches what Disney announced, and I’m reasonably confident is pretty close to the way they calculated it.

Now … keep in mind, however, that within that $190M “loss” is the following:

- $102M paid by Disney Studios (A Disney Entitty) to BV Distribution (A Disney Entity) for their fee

- $33 M interest paid to Disney Corp for interest on the production investment.

- #33 M Studio overhead paid to Disney Studios

So that’s $168M that one could argue isn’t “real” and is more in the realm of Hollywood accounting — although it’s not just Hollywood, all major corporations with various entities and subsidiaries do the same thing.

As noted, there is more income to come — specifically more TV income which will continue for a long time.

There is also the “library value” of the film as an asset. The value of the film will never go down to zero — it will always have some value and perhaps considerable value given its cult following. It may not be “The Wizard of Oz” … but it will continue to have significant value for many years.

So … by Hollywood standards, Disney was probably not being anything but truthful when they estimated $200M loss on John Carter.

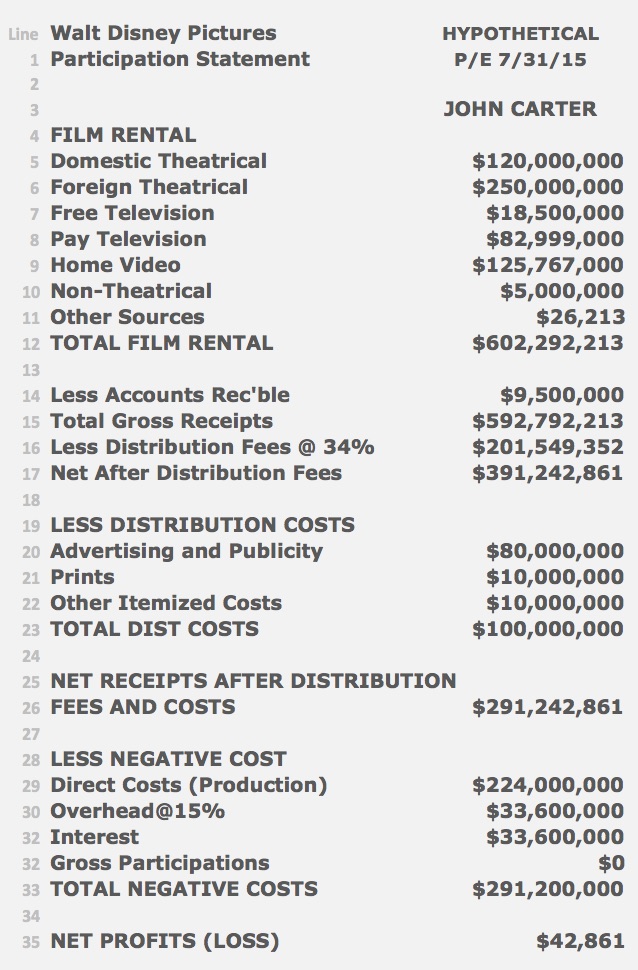

What would it have taken to break even?

Well, sad to say — the one below which just gets into breakeven, is based on worldwide Box Office Gross of around $780M…….depressing, isn’t it? But maybe not as depressing as you think……(see below)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

What this reveals is not only how much JC would have had to make to break even — it also shows that studios regularly greenlight sequels even when the first film is not, by itself, profitable. This is partly because of “Hollywood Accounting”, and partly because when sequels get made, some costs that are entirely absorbed by the first film when it is standalone get spread over more films when it’s a series. Avatar, for example, saw it’s budget go down from whereever it was (high 200’s) to $230M after sequels were greenlit. That means that some of the cost of the original film was shifted to the series. From an accounting point of view this is normal — essentially “R and D Costs” which are one-time costs that accrue to the benefit of the whole series, not just the first film.

So, truly, how much would JC need to have made for Disney to greenlight a sequel?

All things being equal — $500M should have been enough to get a sequel happening, even though that would not have been enough to generate a profit on the first film. Disney would have been able to build profit in over time through all the ancillary things they could do with a successful franchise.

Except …..

Except what?

Except, there was the Star Wars Problem.

Disney bought Star Wars as JC was making it’s run, and that created a different equation, not the normal one. It raised the bar for a John Carter sequel. Disney, having newly acquired Star Wars and fully committed to three new Star Wars movies, had in John Carter a stepchild that, had it landed in the gray area between definite yes and definite no as to a sequel …. would have ended up with a “no” until or unless it performed so well that a sequel just couldn’t be denied.

Oh well, enough of this.

Next time I address this, it will be to do some sensible projections about what it would take for a reboot to be successful.

For now, though — maybe this has provided some insight into the first film’s commercial situation.

===================================================

P.S. If you read all the way to the end of this article, then you really ought to consider buying my book — John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood — just sayin’. . . .

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

“A fair, factual, and enlightening assessment of what went wrong . . . the best corporate history I’ve read since Disney War.” Daniel Butcher, Between Disney.

“A winning book . . . . I have no reservations in recommending John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood. Even if you only remotely hold an interest in the film or the moviemaking method, do yourself a favor and purchase this book. I cannot remember an instance when I read 350 pages of anything in 24 hours, but my level of captivation in how methodically and interestingly the content was presented should substantiate why John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood is a must-read. Grade A.” Brett Nachman, Geeks of Doom.

–

“A must read for every fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs and John Carter and every film buff intrigued by the ‘inside baseball’ aspects of modern Hollywood.” Richard A. Lupoff, Author of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Master of Adventure

“Extensively researched . . . fascinating . . . an engrossing experience, kind of like watching the Titanic headed for the fateful iceberg. Josh Whalen, AmazingStoriesMag.com